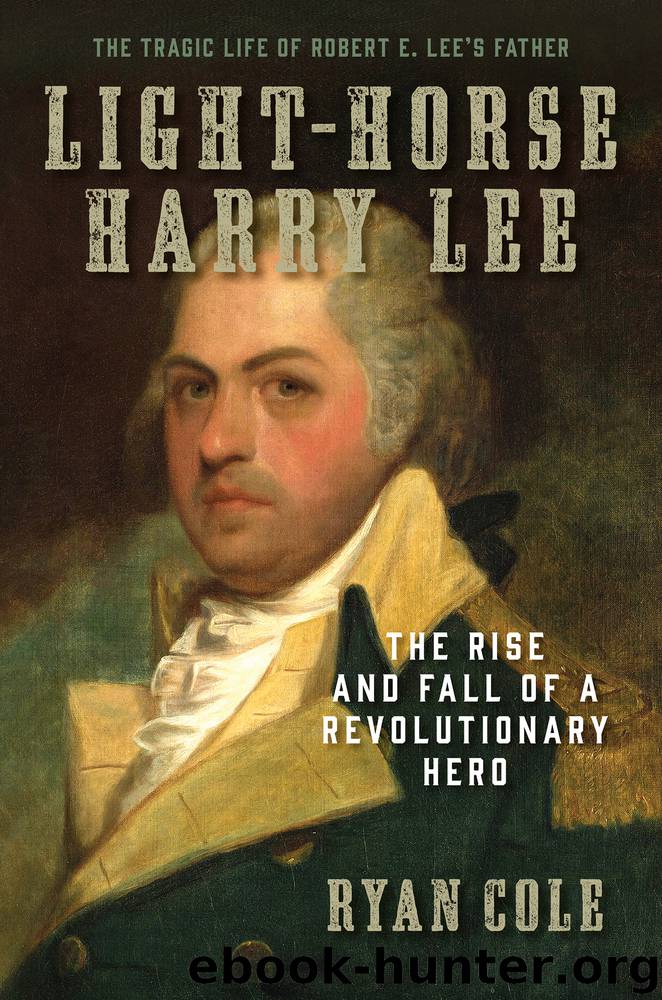

Light-Horse Harry Lee by Ryan Cole

Author:Ryan Cole

Language: eng

Format: epub

Publisher: Regnery History

13

CRACKED

Long before the march to Pittsburg, even before the political tussles over the Constitution, Lee had been promised a golden medal. It was for his exploits during the raid on Paulus Hook, now part of the lore of the American Revolution.

In 1780, the creation of this award, along with six others, had been tasked to Benjamin Franklin, who was to have them struck by Parisian artisans.

But Franklin was only able to commission one medal—for the Frenchman François-Louis Teissèdre de Fleury—before passing the project along, first to David Humphreys and then to Thomas Jefferson. Mysteriously, at some point along the way, Lee’s name was shaved from the list of medal recipients. So when Jefferson returned stateside in 1789 with the finished set, there was no medal for Lee.

Annoyed, Lee approached Jefferson about the omission as early as 1792. Eventually Joseph Wright, the engraver at the newly established U.S. Mint, was tasked with and paid for striking the promised and long-delayed medal. Lee sat for the engraver, who produced a robust profile portrait. But when Wright made the medal, the dye cracked, likely during the hardening process or the actual minting.1 The entire cursed project foreshadowed the coming star-crossed years of Lee’s life, when fleeting magnificence would give way to cruel misfortune.

Certainly no second medal or even commendation was coming for his recent military exploits. “I have become an object of the most virulent enmity of a certain political junto,” Lee stammered days after returning from Pennsylvania, “who affect to govern the U.S. & belch their venom on every Citizen not subservient to their will.”2 The stress was so great, his soul so broken, that Lee was immobilized for a month with a debilitating cold.

The commander in chief of the American army had marched over the mountains, like Hannibal through the alps, and bloodlessly quelled a rebellion against America’s hard-won democratic government. And yet he returned home in the winter of 1795 to find himself a political pariah.

Democratic-Republicans had dared not support the Whiskey Insurrection vocally. Many condemned the rebels, and some, such as John Page, who represented Virginia in Congress, even joined the militia army.3 But many of them were appalled by what they considered the federal government’s grossly disproportionate response. Mustering and marching an army of nearly thirteen thousand into the American hinterlands to squash a pitiful uprising of frustrated and impoverished farmers was the equivalent of exterminating an ant with an anvil. If Democratic-Republicans had not openly supported the rebels, they now criticized the government’s excessive use of force to subdue them.

The outrage that Democratic-Republicans felt towards Lee was articulated in heated prose in the Aurora, whose editor was Benjamin Franklin Bache, the namesake of his grandfather whose words Washington described as “arrows of malevolence.”4 The paper, emptying its quiver, contended that Lee’s proclamation was a partisan screed vilifying the residents of western Pennsylvania for harboring Democratic-Republican-friendly politics, not for actual illegal activity. After all, the Aurora asked, had not Lee himself, less than two years before, “loudly propagated

Download

This site does not store any files on its server. We only index and link to content provided by other sites. Please contact the content providers to delete copyright contents if any and email us, we'll remove relevant links or contents immediately.

Fanny Burney by Claire Harman(26605)

Empire of the Sikhs by Patwant Singh(23089)

Out of India by Michael Foss(16856)

Leonardo da Vinci by Walter Isaacson(13339)

Small Great Things by Jodi Picoult(7148)

The Six Wives Of Henry VIII (WOMEN IN HISTORY) by Fraser Antonia(5518)

The Wind in My Hair by Masih Alinejad(5100)

A Higher Loyalty: Truth, Lies, and Leadership by James Comey(4965)

The Crown by Robert Lacey(4818)

The Lonely City by Olivia Laing(4804)

Millionaire: The Philanderer, Gambler, and Duelist Who Invented Modern Finance by Janet Gleeson(4481)

The Iron Duke by The Iron Duke(4365)

Papillon (English) by Henri Charrière(4277)

Sticky Fingers by Joe Hagan(4204)

Joan of Arc by Mary Gordon(4116)

Alive: The Story of the Andes Survivors by Piers Paul Read(4035)

Stalin by Stephen Kotkin(3971)

Aleister Crowley: The Biography by Tobias Churton(3642)

Ants Among Elephants by Sujatha Gidla(3468)